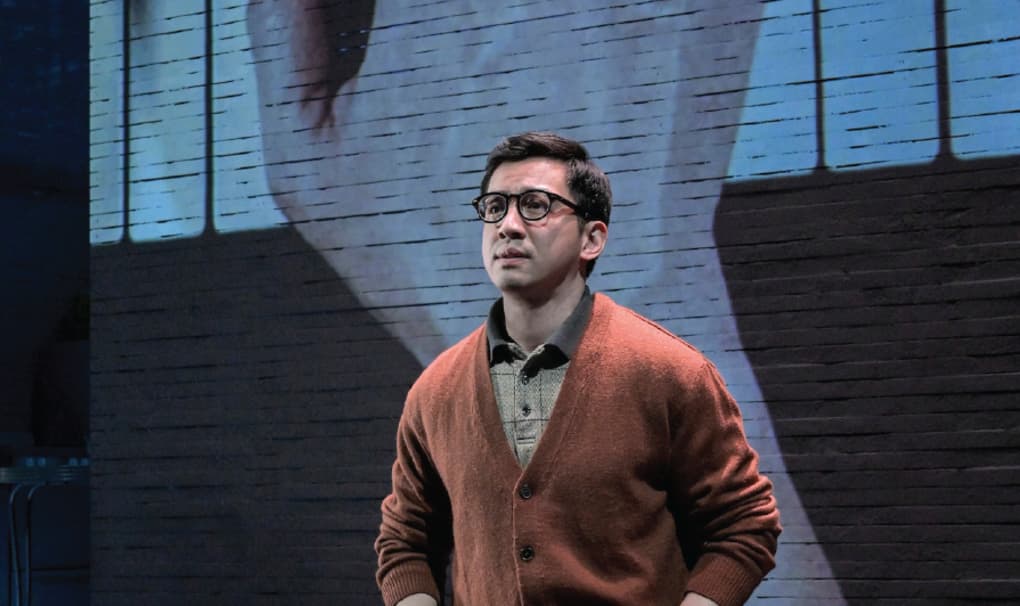

Based in New York City but working around the country, James Ortiz is a designer, performer, playwright, and director, who is most known for his puppet designs in shows like The Woodsman (2016 Obie Award for Puppet Design), Disney’s Hercules (currently at Paper Mill Playhouse before it heads to Broadway), and the most recent Broadway production and now national tour of Into the Woods. For Poor Yella Rednecks, James designed the puppet called Little Man: the 5-year-old personification of the Playwright (played as an adult by Jomar Tagatac), brought to life by actor Will Dao.

Syche Phillips: How did you get started with puppet design and direction?

James Ortiz: I was the painting/drawing/sculpting kid when I was growing up. Around middle school I found my way into theater and that sort of opened me up. In my neighborhood—I’m from a suburb of Dallas—there was a marionette theater that would go around and put on shows like Hansel and Gretel and Jack and the Beanstalk in the public parks. One summer my mother signed me up for it and I took to it right away. I think the reason I was so drawn to it was that it was the Venn diagram center of the things I was excited about: fine arts, character analysis, and performance.

So that’s how I found that interest and fascination, and then I went to an acting conservatory. When I graduated, the first job I got was puppeteering for a puppet opera in New York. One thing led to another and I started making my own work, and I’ve been fortunate to be asked by many interesting organizations to come and work with them. It’s all kind of snuck up on me, really. It’s only been good things.

Syche: How did you get involved with Poor Yella Rednecks?

James: [Director] Jaime [Castañeda] and I have known each other for some time, and we’ve been trying to find a project to work on together. One thing led to another and around 2018, we got into talks about working on this show [A.C.T.’s previously-scheduled 2020 production of Poor Yella Rednecks, canceled due to COVID-19].

So I read the play—I loved the play. It’s rare to find something that is funny, poignant, involves every theatrical convention you can think of, and still hits you like a ton of bricks emotionally. I had some amazing chats with Jaime and we ended up having these conversations less about what the puppet looks like, and more about childhood—and those fleeting, special, complicated moments that you have in those formative years, trying to figure out the world. We definitely started with the psychology first, and then found our way into the aesthetic.

Syche: Tell me about the puppet design for Little Man.

James: Any time you depict a child onstage and, rather than hiring a child actor, you have an adult actor play a kid, or a puppet that represents a kid, the temptation is to go really super saccharine and cutesy. Jaime and I agreed that isn’t something we’re interested in. So first of all, we’re avoiding any material realities that would remind us of a muppet—no felt, no fur. While that look is great and valid and so charming, in a way it becomes a comment on the character, that it’s something that is easily consumable.

In Poor Yella Rednecks, the character is called Little Man because he is a little man, not a boy. He’s quite grown up, and he’s taking in a lot of information. Every scene he’s in is like a kitchen sink drama, and some of the scenes are quite intense and complicated. You can feel that the Playwright is depicting these scenes because these were formative moments for this child.

So that all ties into the aesthetic conversation for the puppet design. We’re going with an old world puppet style, where he’s closer to a wooden puppet. I borrowed from Japanese bunraku, which is a style of really elegant puppetry, among other sources. It’s a little more grounded, a little more tactile, something we can believe in without feeling like it’s silly. He has to be a window into the play. He has to be really transparent even though he doesn’t talk a lot. He’s all the theatrical conventions of the play swirled up into a soup and put into this one character.

Syche: Is Little Man operated entirely by Will Dao?

James: For the most part, Will is the lead puppeteer of the character, but in several scenes, many people will lay hands on him and operate Little Man, or work as additional puppeteers. It sort of depends on what’s expected of him in those scenes—and that’s where we get more theatrical.

Syche: How does the structure of Little Man as a puppet, rather than a child actor, fit into the themes of the show?

James: Qui is obviously really interested in making a play that is a medley of theatricality—it’s a love story to theater. There’s rapping and dancing and narrating...it’s a sprawling canvas of theatrical forms, and sometimes we have scenes that are simple and direct, and other times we’re breaking the fourth wall. In a way, the puppet helps glue all those disparate elements together, because the puppet invites a largesse to any production that you’re working on. Even if it’s a 2-inch little puppet, their appearance onstage invites a larger thematic and visual scale to any show.

Also, by having a group of grown people play a child, you have the opportunity to have really dynamic and interesting conversations about the psychology of a young person, which you may not have the option to do when working with a literal child.

Syche: A lot of times in movies or TV, children feel like props—they come in, say something cute, and then run out of the room and the adults can go on with the “real” story. And that’s just not how kids are in real life. But with this play, Little Man doesn’t feel like a prop. He’s not there so that his parents can be parents—he’s very much there as a character in his own right.

James: Yes, it's really easy to tokenize a child in storytelling. And child actors are often trained to play up the fact that they’re kids. But I think most children don’t think of themselves as children—they want to be seen as little adults. These are all the sorts of things we’re discussing in the room with Will and going, “Yes, the puppet will be cute, but we don’t have to focus on that.” There’s a lot to unpack.

Syche: Your creations run the gamut from large scale puppets that take over the stage, to single characters like Little Man. How does your approach vary between designing Little Man or Milky White, versus something like the larger-than-life puppets for The Tempest or Hercules?

James: It has a lot do with the mission statement of the play, of what the scene wants to get out of the audience, how that affects the design. In a show like Hercules, a lot of that is about spectacle, and recognizing that we’re basically doing the musicalized retelling of Clash of the Titans, so we need to commit to a huge 1980s vision. It has a lot to do with the core idea of the material.

Because so much of the core of Poor Yella Rednecks is a soft-hearted conversation, we couldn’t have done something so big and wild. I guess that’s the main difference in making a big design choice.

Other things also come into play—how many puppeteers do I have? If I have four, I’m going to design a different puppet that has different animation to it. And if the world of the play, meaning the set and costumes and projections, have a certain aesthetic flair, then I have to make sure that what I’m doing belongs inside of that.

Puppets are really weird. The second a puppet appears on stage, the audience immediately goes, “Oh!” It’s a little bit like when you see a Shakespeare play, and in the first 10 minutes there’s a chunk of the audience who is catching up with the language. In a fun way that does happen with a puppet too—as an audience member, we have to take in how it’s being worked and all of that. Puppets can easily stand out like a sore thumb. I spend a lot of time making sure the puppets belong in the fabric of the play itself.

Syche: What’s your dream puppet project?

James: I’ve always had my own weird rules around what show “deserves” a puppet and what doesn’t, but as the years go by I find my rules are breaking. There was a long time where I would have said, “There’s no way you could ever have a puppet in Death of a Salesman”…but then you think about it, and I bet there’s a way. There’s a notion that I’m in early days with—doing a one man show retelling of The Glass Menagerie where Tom is the only actor onstage and the rest are sort of tabletop porcelain characters.

Syche: I LOVE that.

James: Wouldn’t that be beautiful? And of course, you’re begging to break Laura at some point.

I’m also a huge cinephile and a sci fi dork, so I love any time I get to engage with some of those flavors onstage. Hercules was such a gift in that way, because I’m…responsible for making fantasy monsters? How exciting! I’m about to go into a wildly different design for Little Shop of Horrors at The Muny this summer, and the fun of it is pulling from a lot of camp, horror films, and sci-fi B movies from the 50s and 60s and 70s, and asking ourselves, “But what would be really different and kind of gross?” We’re having a really fun time with that.

I have lots of fun ideas about trying to push theatrical genre around. I guess my dream project is usually the one I’m currently working on.

Learn more about Poor Yella Rednecks: Vietgone 2, running Mar 30–May 7 at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater.